Maximal Entropy of the Boltzmann Distribution: A Quantum Perspective

Specifically, in the classical limit (when βEn << 1), the quantum energy levels become very close to each other, and the partition function can be approximated by an integral over continuous energy states rather than a sum over discrete states. In this limit, the quantum Boltzmann distribution approaches the classical result...

Introduction

In statistical physics, the Boltzmann distribution is one of the most fundamental and widely applied concepts. It describes how particles in a system—whether gas molecules, atoms, or even subatomic particles—distribute themselves among different energy states in thermal equilibrium. This simple-looking equation, however, is far more than just a tool for calculating temperature or pressure; it links the microscopic, quantum behavior of individual particles to the macroscopic thermodynamic properties we observe in everyday life.

But how exactly do we derive this distribution? While it’s commonly presented as a well-known result, the path to its formulation is anything but straightforward. The Boltzmann distribution doesn’t emerge from any single law of nature, but from a set of assumptions and principles. One of the key principles behind its derivation is the maximum entropy principle, a concept that originates in information theory but has profound implications in statistical mechanics.

Information theory must precede probability theory and not be based on it.

\(~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~\) \(~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~\)by Andrey Nikolaevich Kolmogorov

At its core, the maximum entropy principle suggests that, when constrained by known macroscopic quantities like energy or particle number, the most probable state of a system is the one that maximizes the system’s entropy. In simpler terms, the most likely distribution of particles is the one that reflects the greatest uncertainty about the system’s microscopic state, given the constraints we have. This approach not only provides a way to derive the Boltzmann distribution but also unites classical and quantum statistical mechanics.

In classical systems, where particles can occupy continuous energy levels, the Boltzmann distribution directly describes how particles are spread across those levels. But in the quantum world, where particles are confined to discrete energy states, the situation becomes more complex. The introduction of the Quantum Canonical Ensemble allows us to extend the classical Boltzmann distribution into the quantum domain, where energy quantization and other quantum effects must be taken into account.

In the following sections, we’ll explore how the maximum entropy principle provides the key to deriving the Boltzmann distribution, and how it can be extended to the quantum realm through the Quantum Canonical Ensemble.

Nov 28, 2024: Some of the quantum concepts mentioned in this article give me an excuse to shamelessly plug my upcoming paper, “Quantum Reinforcement Learning for 🫣,” particularly the preliminary section. It’s currently undergoing major revision—stay tuned!

Maximizing Entropy: Deriving the Boltzmann Distribution

In the quest to uncover the probability distribution that governs a system in thermodynamic equilibrium, we turn to the principle of maximum entropy. This elegant idea, first formulated in information theory, tells us that the best description of a system’s state is the one that maximizes uncertainty—subject to the constraints we know about the system. In statistical mechanics, those constraints often relate to conserved quantities like total particle number or average energy.

Let’s begin by considering a system with a set of discrete energy levels $ { \epsilon_i }_{i=1}^N $. Our goal is to find the probability distribution $ { p_i } $ that describes the likelihood of the system occupying each energy level $ \epsilon_i $, with the constraint that the total probability sums to one, and the system has a fixed average energy.

Measuring Uncertainty

To quantify this uncertainty, we use Shannon entropy. The entropy of a probability distribution $ { p_i } $ is defined as:

\[S = -k_B \sum_{i=1}^N p_i \ln p_i,\]where $ k_B $ is the Boltzmann constant. This formula captures the degree of disorder or uncertainty within the system—the more uncertain we are about the system’s microstate, the higher the entropy.

Of course, you can also use other definitions or designed entropies, because the logarithmic function is not determined by the entropy itself, but rather by how we approximate entropy based on the variation properties of different functions according to personalized needs.

Our task is to find the distribution $ { p_i } $ that maximizes this entropy, while also satisfying two important constraints:

-

Normalization: The total probability must sum to one:

\[\sum_{i=1}^N p_i = 1.\] -

Energy constraint: The system’s average energy must be fixed at some value $ U $:

\[\langle E \rangle = \sum_{i=1}^N p_i \epsilon_i = U.\]

The Lagrange Multiplier Method

To incorporate these constraints, we use Lagrange multipliers. We want to maximize the entropy $ S $ subject to the above constraints, so we introduce two Lagrange multipliers, $ \alpha $ (for the normalization constraint) and $ \beta $ (for the energy constraint). We now define the Lagrangian functional $ \mathcal{L} $ as:

\[\mathcal{L} = -k_B \sum_{i=1}^N p_i \ln p_i - \alpha \left( \sum_{i=1}^N p_i - 1 \right) - \beta \left( \sum_{i=1}^N p_i \epsilon_i - U \right).\]We seek the values of $ p_i $ that make $ \mathcal{L} $ stationary, which we do by differentiating with respect to $ p_i $ and setting the result equal to zero. The partial derivative of $ \mathcal{L} $ with respect to $ p_i $ is:

\[\frac{\partial \mathcal{L}}{\partial p_i} = -k_B (1 + \ln p_i) - \alpha - \beta \epsilon_i = 0.\]Solving for $ p_i $, we get:

\[\ln p_i = -1 - \frac{\alpha}{k_B} - \frac{\beta}{k_B} \epsilon_i,\]which simplifies to:

\[p_i = C e^{-\frac{\beta}{k_B} \epsilon_i},\]where $ C $ is a constant to be determined later. This form suggests that the probability $ p_i $ is exponentially related to the energy $ \epsilon_i $, which is exactly what we expect from a system in equilibrium.

For the details and principles of the Lagrange multiplier method, you can refer to any textbook on operations research and optimization.

Here, we just used it as a tool for solving the problem. En réalité, j’ai un véritableement brillant raisonnement pour cette proposition, mais cette marge est bien trop étroite pour le contenir. 😎

Determining the Constant $ C $

To find the constant $ C $, we use the normalization condition. Summing over all states, we require that:

\[\sum_{i=1}^N p_i = 1.\]Substituting the expression for $ p_i $, we obtain:

\[\sum_{i=1}^N C e^{-\frac{\beta}{k_B} \epsilon_i} = 1.\]This implies that $ C $ must be:

\[C = \frac{1}{Z},\]where $ Z $ is the partition function defined as:

\[Z = \sum_{i=1}^N e^{-\frac{\beta}{k_B} \epsilon_i}.\]Thus, the probability distribution that maximizes entropy, subject to the constraints, is:

\[p_i = \frac{e^{-\frac{\beta}{k_B} \epsilon_i}}{Z}.\]This is the Boltzmann distribution, where $ \beta $ is a constant related to the temperature $ T $ by $ \beta = \frac{1}{k_B T} $. This result tells us that the likelihood of the system being in a particular state is exponentially weighted by the energy of that state, with higher-energy states being exponentially less probable than lower-energy states at higher temperatures.

Physical Interpretation

The Boltzmann distribution not only maximizes the entropy but also satisfies the energy constraint: the average energy of the system $ \langle E \rangle $ is the weighted sum of the energies of the individual states, with the Boltzmann distribution providing the correct weighting. The factor $ \beta $ controls the distribution’s dependence on energy and temperature, with $ \beta $ decreasing as the temperature increases, meaning that at high temperatures, the system is more likely to occupy higher-energy states.

We can also gain deeper insight into the partition function $ Z $. It plays a central role in thermodynamics, encapsulating all the information about the system’s statistical properties. In fact, the partition function is directly related to the Helmholtz free energy $ F $, which governs the system’s thermodynamic behavior:

\[F = -k_B T \ln Z.\]From this, we can derive other thermodynamic quantities, like entropy $ S $ and internal energy $ U $, by differentiating $ F $ with respect to temperature or other variables.

Demo

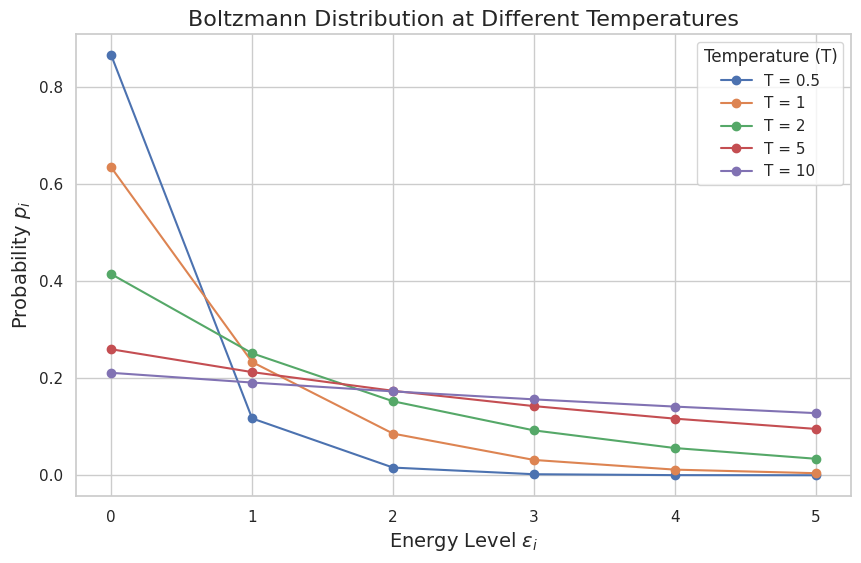

Now that we’ve mathematically derived the Boltzmann distribution using the maximum entropy principle, let’s bring that theory to life with a simple Demo. The goal here is to simulate how the distribution behaves at different temperatures and visualize how particles are more likely to occupy higher energy states as temperature increases.

We’ll model a system with discrete energy levels $ \epsilon_i $ (let’s use values from 0 to 5 for simplicity). Our main task is to compute the probabilities $ p_i $ for each energy level using the Boltzmann distribution:

\[p_i = \frac{e^{-\frac{\beta}{k_B} \epsilon_i}}{Z},\]where $ \beta = \frac{1}{k_B T} $ and $ Z $ is the partition function:

\[Z = \sum_{i=1}^N e^{-\frac{\beta}{k_B} \epsilon_i}.\]

What you’ll notice is that at low temperatures (e.g., $ T = 0.5 $), the distribution is sharply peaked at the lowest energy level—most particles occupy the ground state. As the temperature increases (e.g., $ T = 10 $), the distribution spreads out, and the probability of occupying higher energy states increases. This is the Boltzmann distribution in action: at higher temperatures, particles are more likely to be found in higher energy states because there is less exponential suppression of those states.

Quantum Canonical Ensemble Derivation of the Boltzmann Distribution

After deriving the classical Boltzmann distribution using the maximum entropy principle, we’ve arrived at a powerful tool for understanding systems in thermal equilibrium. But here’s where things get really interesting: what happens when we shift our attention from classical to quantum systems? Classical statistics, as we know, assumes that energy levels are continuous, particles behave as distinguishable entities, and the laws of thermodynamics apply seamlessly. However, quantum systems operate under different rules, with discrete energy levels, indistinguishable particles, and, crucially, quantum mechanical phenomena like superposition and entanglement.

From Classical to Quantum

In classical systems, the energy levels are treated as continuous, and particles are distinguishable. For example, in classical thermodynamics, the system’s behavior is described by average quantities (like pressure, volume, and temperature) that emerge from statistical averages over all possible microstates. But when dealing with quantum systems, things get much more intricate.

Quantum systems are governed by a Hilbert space, where the energy states are discrete, and the particles are indistinguishable. This means the states of the system are no longer described by simple averages but by a density operator. Furthermore, quantum systems obey the Pauli exclusion principle (for fermions) or Bose-Einstein statistics (for bosons), which impose additional constraints on how particles can occupy different energy states.

In quantum statistical mechanics, we must therefore account for these discrete states and their probabilistic occupation. Rather than dealing with a smooth distribution over energy states, we deal with specific quantum states, each of which has a corresponding energy eigenvalue $ E_n $. These eigenstates $ \vert n \mathpunct{\rangle} $ can be occupied with different probabilities depending on the temperature, which leads us to the concept of the partition function and the density matrix.

The Quantum Partition Function

In quantum statistical mechanics, the partition function plays a similar role to what it did in the classical derivation of the Boltzmann distribution. However, in quantum systems, we express this as a sum over all possible quantum states, each weighted by a factor related to its energy:

\[Z = \sum_n e^{- \beta E_n},\]where $ Z $ is the quantum partition function, $ \beta = \frac{1}{k_B T} $ is the inverse temperature, and $ E_n $ are the energy eigenvalues of the system. This sum takes into account all possible quantum states, where the probability of being in a particular state $ \vert n \mathpunct{\rangle} $ depends on its energy $ E_n $.

The density operator $ \hat{\rho} $, which describes the quantum state of the system, is given by:

\[\hat{\rho} = \frac{1}{Z} e^{-\beta \hat{H}},\]where $ \hat{H} $ is the Hamiltonian operator (which encapsulates the total energy of the system). The density operator governs the probability distribution of the system’s quantum states, and we can calculate the probability $ P_n $ of finding the system in state $ \vert n \mathpunct{\rangle} $ as:

\[P_n = \langle n | \hat{\rho} | n \rangle = \frac{e^{- \beta E_n}}{Z}.\]Deriving the Quantum Boltzmann Distribution

Now that we have the quantum density matrix $ \hat{\rho} $, the next step is to derive the quantum version of the Boltzmann distribution. For a system in thermal equilibrium, the probability of the system occupying a particular quantum state $ |n \mathpunct{\rangle}$ with energy $ E_n $ is given by:

\[P_n = \frac{e^{- \beta E_n}}{Z}.\]This is the same formula as the classical Boltzmann distribution, but with one crucial difference: it arises in a quantum context, where the states $ \vert n \mathpunct{\rangle} $ are discrete and represent the quantum states of the system. Importantly, the partition function $ Z $ accounts for the normalization of the system over all possible states, ensuring that the total probability sums to 1.

In quantum systems, the partition function $ Z $ is not just a mathematical convenience—it’s a central thermodynamic quantity. It encapsulates all the thermal information of the system, allowing us to derive quantities such as the average energy, entropy, and even the free energy. The internal energy $ U $, for example, is given by:

\[U = \langle \hat{H} \rangle = \frac{1}{Z} \sum_n E_n e^{-\beta E_n}.\]This quantity, $ U $, provides the average energy of the system, weighted by the Boltzmann factor $ e^{-\beta E_n} $. Similarly, the entropy $ S $ of the system can be derived from the density matrix, and is given by:

\[S = -k_B \sum_n P_n \ln P_n = k_B \left( \ln Z + \beta \langle E \rangle \right).\]Recovering the Classical Limit

At this point, we’ve arrived at the quantum Boltzmann distribution:

\[P_n = \frac{e^{- \beta E_n}}{Z}.\]But how do we connect this result to the classical case? The answer lies in the high-temperature limit. As temperature $T$ increases, the quantum system behaves more and more like a classical system. Specifically, in the classical limit (when $ \beta E_n \ll 1 $), the quantum energy levels become very close to each other, and the partition function can be approximated by an integral over continuous energy states rather than a sum over discrete states. In this limit, the quantum Boltzmann distribution approaches the classical result:

\[P_n \approx \frac{e^{-\beta E_n}}{Z_{\text{classical}}}.\]This recovery of the classical Boltzmann distribution from the quantum framework illustrates the seamless transition from quantum to classical statistics as the temperature increases and the system becomes large.

Demo

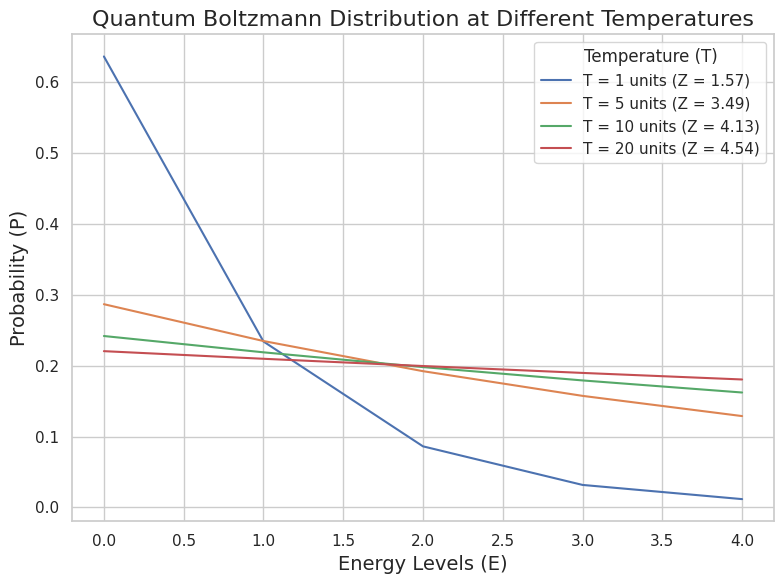

Now that we’ve got a solid understanding of how the quantum Boltzmann distribution works, let’s see it in action. We’ll simulate a system of particles that can occupy discrete energy levels, and use Python to calculate and plot the probability of each energy state at various temperatures.

In quantum mechanics, things get interesting because energy levels are discrete. This means particles in a system can only occupy specific energy states. The Boltzmann distribution in this context gives us the probability of a system being in a particular state, and it’s influenced by temperature. The cooler the system, the more likely it is to find particles in the lower energy states. As the temperature rises, particles are more likely to occupy higher energy states.

We’ll work with a simple system of five energy levels, ranging from 0 to 4 (in arbitrary units), and observe how the distribution of particles shifts as we change the temperature.

In the code, we define the energy levels and compute the Boltzmann distribution for different temperatures. The partition function $ Z $ normalizes the distribution, ensuring that the total probability across all states sums to 1. At each temperature, we calculate the probability of the system being in each energy state and plot it.

At low temperatures, the particles prefer the lower energy states, so you’ll see a sharp peak at $ E = 0 $. As the temperature increases, the distribution flattens out, meaning particles are more evenly spread across the available energy states. At high temperatures, the system behaves almost classically, with probabilities becoming more uniform across the states.

If you push the temperature high enough, the quantum effects start to blur out. The system behaves less quantum-mechanically and more classically—particles are equally likely to be found in any state. This is where quantum and classical statistics start to converge, and the Boltzmann distribution recovers its classical form.

Conclusion

Along the way, we explored how the seemingly simple concept of entropy can elegantly extend from classical to quantum systems, providing us with the tools to model everything from gas particles to quantum states in thermal equilibrium.

Of course, I’ll be the first to admit that this is far from a perfect or complete explanation. Some of the math might feel a bit rushed, and the logic may not always be as sharp as it should be. Frankly, I’m still wrapping my head around some of these ideas myself. So, if you’re an expert (or even if you’re not), feel free to call me out—I’m sure there are plenty of rough edges that need smoothing over. This is a work in progress, not the final word. 🌎