Sampling Smarter: Unlocking the Power of Latin Hypercube Sampling

What is Latin Hypercube Sampling?

Imagine you’re standing over a large chessboard, each square representing a potential outcome of some experiment. The squares are spread out, spanning the entire board, and the goal is to gather a sample of outcomes that gives you the best possible understanding of the whole chessboard—not just a corner, not just a few scattered patches, but everywhere. Latin Hypercube Sampling (LHS) is a smart way to do this, ensuring that each row and column of the board has exactly one selected square. It’s like a carefully orchestrated game where you end up with one piece in every row and every column, giving you a complete sense of the landscape. In the world of data science, this chessboard metaphor expands into multidimensional space. Instead of just two dimensions—like the chessboard’s rows and columns—think of an entire universe of variables, each one adding a new dimension. If you’re trying to model something complex, like how different factors affect climate or how various inputs influence the outcome of an engineering system, you need a way to efficiently sample from all these different dimensions.

That’s where LHS shines. Unlike random sampling, which might leave some regions underrepresented while others get chosen repeatedly, LHS spreads the samples evenly across each dimension. Think of it as ensuring every corner of the universe of possibilities gets its fair share of attention. Each sample is like a probe that’s perfectly positioned to gather information from every aspect of the system, without clustering too much in any one place.

The key idea behind LHS is balance—the same kind of balance you see when picking one square from each row and column on the chessboard. In a higher-dimensional space, this means that every slice, or segment, of each variable range is covered, guaranteeing that the entire spectrum of potential values is represented. Whether you’re dealing with three variables or thirty, LHS keeps the sampling efficient and comprehensive, giving you a representative cross-section of all possible outcomes without redundancy or waste. This balanced sampling can be crucial in many practical applications. Imagine trying to predict the success of a new product launch by varying factors like price, marketing budget, and target audience. With LHS, you’re not just randomly throwing darts; you’re making sure that every aspect—from low budgets to high, from niche audiences to broad appeal—is represented in a structured way. The end result? A clearer picture of how each factor interacts, and ultimately, better insights and more informed decisions.

LHS isn’t just about getting data—it’s about getting the right data, the kind that captures complexity without unnecessary repetition. In the chapters ahead, we’ll dive deeper into how LHS works in practice, explore its benefits, and compare it to other sampling methods, illustrating why this approach has become a favorite among statisticians and engineers alike.

Why Do We Need Latin Hypercube Sampling?

LHS is a powerful tool for efficiently understanding complex systems when resources are limited. In the real world, whether we are studying natural phenomena, building financial models, or designing new technology, we often face too many possible combinations of factors to analyze exhaustively. LHS provides a smart way to sample the most relevant data without having to examine every possibility.

Think of tasting a big pot of vegetable soup. If you randomly scoop just once, you might get mostly broth or only one type of vegetable, missing the full flavor. LHS ensures that each spoonful represents every major ingredient, giving a balanced understanding of the whole pot. Similarly, LHS ensures that every part of a complex system is represented, giving us a clearer, more complete picture. This method is particularly useful in high-dimensional problems, like understanding energy consumption in a building, which depends on factors such as temperature, occupancy, lighting, and insulation. Random sampling might leave some factor combinations out, leading to gaps in understanding. LHS ensures that all relevant combinations are covered, making it easier to see the relationships without redundant or overlooked data. The efficiency of LHS is one of its biggest advantages. For instance, in modeling the effects of a new drug, with many variables like dosage and genetic markers, LHS allows for fewer, but strategically chosen, trials that still provide a comprehensive view. This means we can extract meaningful insights without the need for an overwhelming number of experiments.

In practical applications, whether constrained by budget, time, or logistics, LHS proves invaluable. Engineers can use it to test a manageable number of car engine configurations, while scientists can employ it to study pollutant spread efficiently. LHS provides a strategic way to cover the landscape, ensuring no critical area is neglected.

How Does Latin Hypercube Sampling Work?

To truly understand LHS and appreciate its unique capabilities, we’ll delve into the mathematics underpinning it. Through a sequence of structured steps, we’ll see how LHS ensures efficient, balanced sampling in multidimensional space. This method systematically constructs sample points to provide a representative cross-section of complex systems, thereby capturing the essence of multidimensional data without unnecessary redundancy.

1. Problem Setup

Consider a \(d\)-dimensional parameter space where each parameter \(x_i\) can take values within a defined interval \([a_i, b_i]\). Our objective is to generate \(N\) distinct sample points \(x^{(1)}, x^{(2)}, \dots, x^{(N)}\), where each \(x^{(k)} = (x_1^{(k)}, x_2^{(k)}, \dots, x_d^{(k)})\) lies within this \(d\)-dimensional space. The challenge is to arrange these sample points such that they collectively cover the entire parameter space in a balanced and representative manner, avoiding clusters or sparse areas.

2. Dividing Each Dimension into Intervals

For each dimension \(x_i\), we begin by dividing the interval \([a_i, b_i]\) into \(N\) non-overlapping subintervals. Formally, we can define these intervals as:

\[[a_i, b_i] = \bigcup_{j=1}^N \left[ a_i + \frac{j-1}{N} (b_i - a_i), a_i + \frac{j}{N} (b_i - a_i) \right]\]where each subinterval \(I\_{i,j}\) for dimension \(x_i\) is given by:

\[I_{i,j} = \left[ a_i + \frac{j-1}{N} (b_i - a_i), a_i + \frac{j}{N} (b_i - a_i) \right]\]The length of each interval, \(\Delta x_i\), is consistent across \(x_i\):

\[\Delta x_i = \frac{b_i - a_i}{N}\]This systematic partitioning ensures that each dimension \(x_i\) is split into \(N\) equal sections, which lays the groundwork for comprehensive sampling.

3. Random Sampling within Each Interval

Within each subinterval \(I*{i,j}\) of dimension \(x_i\), we randomly select a point \(x*{i,j}\). This point can be represented mathematically as:

\[x_{i, j} = a_i + \frac{j-1}{N} (b_i - a_i) + U_{i,j} \cdot \Delta x_i\]where \(U*{i,j} \sim \text{Uniform}(0,1)\) represents a uniformly distributed random variable within \([0,1]\). This formulation ensures that \(x*{i,j}\) falls randomly within the subinterval \(I\_{i,j}\), providing a sample point that respects the interval boundaries.

4. Constructing Multidimensional Sample Points

To generate the complete set of \(N\) sample points in \(d\)-dimensional space, we must combine these dimension-specific sample points. This is done by assigning each sample from \(x_i\) to a unique subinterval in each dimension using a random permutation function \(\pi_i\). The permutation \(\pi_i\) for each dimension \(x_i\) randomly orders the indices \(\{1, 2, \dots, N\}\) such that each subinterval is represented exactly once.

The \(k\)-th sample point in \(d\)-dimensional space is thus constructed as:

\[x^{(k)} = \left( x_{1, \pi_1(k)}, x_{2, \pi_2(k)}, \dots, x_{d, \pi_d(k)} \right)\]This arrangement guarantees that each sample point spans a unique combination of subintervals across all dimensions, achieving an even spread and complete coverage of the parameter space.

5. Proof of Marginal Uniformity

One of the core strengths of LHS lies in its marginal uniformity. This property ensures that the samples are uniformly distributed along each individual dimension \(x_i\), even as they span multiple dimensions. Let’s delve into a formal explanation:

- Each dimension \(x*i\) is divided into \(N\) intervals \(I*{i,1}, I*{i,2}, \dots, I*{i,N}\), with a single sample \(x\_{i,j}\) taken from each interval.

- Each sample \(x\_{i,j}\) is drawn uniformly from within its interval, meaning that the probability of sampling any particular region within \([a_i, b_i]\) is evenly distributed.

- Consequently, for each dimension \(x_i\), the probability distribution of the sample points across intervals is uniform, with each subinterval receiving exactly one sample point.

This uniformity across intervals ensures that the samples are well-distributed along each dimension, resulting in comprehensive and unbiased coverage of the space.

6. Variance Reduction in Latin Hypercube Sampling

An essential advantage of LHS is its ability to reduce variance in the estimated outcomes, particularly when compared to simple random sampling (SRS). This reduction in variance leads to more accurate estimations with fewer samples. To illustrate this, we consider the variance of the sample mean \(\hat{f}\) when estimating the expectation \(\mathbb{E}[f(x)]\) for a function \(f(x)\) over our \(d\)-dimensional space.

Given \(f(x)\), the sample mean \(\hat{f}\) based on \(N\) samples is:

\[\hat{f} = \frac{1}{N} \sum_{k=1}^N f(x^{(k)})\]We can express the variance of \(\hat{f}\) as:

\[\text{Var}(\hat{f}) = \frac{1}{N^2} \sum_{k=1}^N \sum_{l=1}^N \text{Cov}(f(x^{(k)}), f(x^{(l)}))\]In LHS, because each sample point \(f(x^{(k)})\) is drawn independently across distinct subintervals, the covariance \(\text{Cov}(f(x^{(k)}), f(x^{(l)}))\) for \(k \neq l\) is zero. This simplifies the variance expression to:

\[\text{Var}(\hat{f}) = \frac{1}{N^2} \sum_{k=1}^N \text{Var}(f(x^{(k)}))\]Result: Variance Reduction in LHS

Since each sample \(f(x^{(k)})\) is uniformly distributed across the intervals, the variance in LHS is inherently reduced compared to simple random sampling. In SRS, the variance is:

\[\text{Var}_{\text{SRS}}(\hat{f}) = \frac{\sigma^2}{N}\]where \(\sigma^2\) represents the population variance of \(f(x)\). In contrast, LHS ensures that each dimension’s intervals are well-covered, which results in:

\[\text{Var}_{\text{LHS}}(\hat{f}) \leq \frac{\sigma^2}{N}\]This inequality demonstrates that LHS consistently achieves lower variance than simple random sampling, making it a more efficient and precise sampling method.

Example: Optimizing a Drug Dosage Experiment with LHS

To truly appreciate how LHS works, let’s dive into a practical example in drug dosage research. Suppose we’re conducting a study to understand how different drug doses, patient ages, and body weights affect blood concentration levels. Instead of relying on simple random sampling, which might overlook certain important combinations, LHS allows us to achieve balanced sampling across multiple dimensions, making the experiment both efficient and insightful.

Experiment Setup and Goals

In this study, we have three key variables:

- Dosage (\(x_1\)): Ranges from \([50, 200]\) mg.

- Age (\(x_2\)): Ranges from \([20, 80]\) years.

- Weight (\(x_3\)): Ranges from \([50, 100]\) kg.

Our goal is to generate \(N = 5\) sample points that represent this multi-dimensional space well, ensuring each factor’s range is adequately covered. This approach will allow us to identify patterns without conducting an exhaustive set of tests.

Step 1: Dividing Each Dimension into Intervals

With \(N = 5\) samples, we divide each variable’s range into five non-overlapping intervals:

-

Dosage (\(x_1\)): The range \([50, 200]\) mg is divided into five intervals of length \(\Delta x_1 = \frac{200 - 50}{5} = 30\) mg:

\[[50, 80], [80, 110], [110, 140], [140, 170], [170, 200]\] -

Age (\(x_2\)): The range \([20, 80]\) years is divided into five intervals of length \(\Delta x_2 = \frac{80 - 20}{5} = 12\) years:

\[[20, 32], [32, 44], [44, 56], [56, 68], [68, 80]\] -

Weight (\(x_3\)): The range \([50, 100]\) kg is divided into five intervals of length \(\Delta x_3 = \frac{100 - 50}{5} = 10\) kg:

\[[50, 60], [60, 70], [70, 80], [80, 90], [90, 100]\]

This structured partitioning provides a foundation for balanced sampling within each dimension.

Step 2: Random Sampling within Each Interval

Next, we randomly select a sample point within each subinterval. For example, within the first dosage interval \([50, 80]\), we select a random point \(x\_{1,1}\). We do the same for other intervals, ensuring a point is chosen within each range. This process guarantees that every segment of each variable’s range contributes to our sample set.

Let’s say we get the following randomly chosen points for each dimension:

- Dosage (\(x_1\)): 63, 94, 125, 157, 189

- Age (\(x_2\)): 24, 39, 50, 63, 76

- Weight (\(x_3\)): 52, 66, 78, 85, 93

Step 3: Constructing Multi-Dimensional Sample Points

To create our final five sample points in three-dimensional space, we combine these points by applying random permutations to each dimension. For example, we can randomly shuffle each dimension’s values, resulting in the following combinations:

- Dosage permutation: 125, 63, 189, 94, 157

- Age permutation: 63, 24, 76, 39, 50

- Weight permutation: 66, 78, 93, 52, 85

Thus, our final sample points are:

\[(125, 63, 66)\] \[(63, 24, 78)\] \[(189, 76, 93)\] \[(94, 39, 52)\] \[(157, 50, 85)\]Step 4: Evaluating the Balance of Our Sample Set

This arrangement ensures that each variable is evenly represented across its range. Every sample point combines different segments of each dimension, avoiding excessive clustering in any one area. Compared to simple random sampling, LHS guarantees a well-rounded representation of our parameter space, which is critical for accurately studying relationships between variables.

Analyzing the Results

In this example, LHS allows us to effectively sample a three-dimensional space, covering a comprehensive range of dosage, age, and weight combinations with only five samples. This balanced approach gives us a holistic view of how these variables interact, helping researchers understand dosage effects across diverse patient profiles while minimizing experimental overhead.

Real-World Applications of Latin Hypercube Sampling

LHS may sound like a tool for abstract math, but its practical impact is very real. Across engineering, environmental science, finance, healthcare, and energy modeling, LHS is a quietly transformative technique, allowing researchers to gain clear insights without drowning in data. Imagine trying to paint a detailed landscape but having only a handful of colors and brushstrokes to work with—LHS is like using those few strokes in exactly the right places to capture the whole scene with remarkable accuracy. Here’s how LHS works its magic across different fields.

In engineering, for example, LHS helps streamline design and testing. Think of a car manufacturer simulating thousands of design combinations to improve performance under diverse conditions like temperature, load, and speed. Instead of running endless trials, LHS allows engineers to test a fraction of those designs in a structured way, covering the full range of conditions without redundancy. The result? They get the insights needed to enhance performance with far fewer tests, saving time and resources without sacrificing precision.

Environmental science is another area where LHS is indispensable. Imagine trying to model how pollutants might spread across a city. Factors like wind speed, direction, and geographic features all interact to shape pollution patterns. With LHS, researchers can simulate these combinations in a balanced way, ensuring that different scenarios are well represented without oversampling any particular case. This approach not only sharpens predictions but also provides critical insights for health policies and urban planning—essential when resources are tight, but accuracy is crucial.

Finance is yet another domain where LHS proves its worth, especially in risk analysis. Financial analysts need to understand how a portfolio might behave across a range of market conditions—interest rates, currency fluctuations, inflation, and so on. Rather than randomly selecting scenarios, LHS strategically samples across these factors, capturing both typical and extreme market conditions. This balanced approach provides a clearer risk profile and enables better-informed investment decisions, all while keeping data requirements manageable.

In healthcare, LHS is a valuable ally in clinical trials and biomedical research. Imagine testing a new drug across diverse patient characteristics like age, genetic profile, and lifestyle. Testing every combination is impossible, so LHS helps researchers select a representative set of patient scenarios. By covering each variable without redundancy, LHS ensures that no group is overlooked, giving a comprehensive view of the drug’s impact across different demographics, often revealing critical insights early on.

Even energy modeling for buildings benefits from LHS. When designing sustainable buildings, architects need to know how energy usage changes based on insulation, occupancy, weather, and other factors. LHS allows for sampling across these variables in a way that efficiently covers the range of possible conditions. By using LHS to model these combinations, analysts can optimize energy efficiency without testing every single scenario, resulting in smarter, greener design choices.

In each of these fields, LHS is the secret ingredient that transforms limited samples into broad, balanced insights, ensuring that complex systems are thoroughly represented without overwhelming resources. It’s a perfect example of sampling smarter, not harder, proving that sometimes, a carefully chosen subset can be just as powerful as an exhaustive dataset. As data-driven decisions become more central to progress, LHS is one tool that ensures those decisions are both efficient and well-informed.

Limitations of Latin Hypercube Sampling

While LHS is a remarkably efficient method for capturing multidimensional data, it has limitations, particularly when dealing with high-dimensional spaces and dynamic systems. These challenges underscore that even advanced sampling techniques like LHS must sometimes be augmented or adapted to maintain efficiency and accuracy.

Computational Demands in High Dimensions

One of the primary challenges with LHS arises in high-dimensional spaces. As the number of dimensions \(d\) grows, the complexity of generating \(N\) samples with balanced coverage across each dimension increases significantly. In lower-dimensional spaces, LHS achieves a clear advantage by ensuring that every interval in each dimension is represented. However, as \(d\) rises, this method begins to experience what’s known as the “curse of dimensionality,” where the sample space becomes exponentially large.

To understand this more formally, consider that LHS divides each dimension’s interval into \(N\) equal parts, requiring \(N^d\) unique combinations to ensure complete coverage in the \(d\)-dimensional space. However, practical constraints often limit the total number of samples \(N\), leading to fewer possible combinations in the high-dimensional setting, which means that not all regions of the space are sampled as evenly. When the sampling coverage is incomplete, the variance reduction properties of LHS also diminish. The variance of a sample mean \(\hat{f}\) from LHS in high-dimensional spaces approximates as:

\[\text{Var}_{\text{LHS}}(\hat{f}) \approx \frac{\sigma^2}{N} \cdot \left( 1 + \frac{d - 1}{N} \right)\]where \(\sigma^2\) is the population variance. This variance formula highlights that as \(d\) approaches \(N\), variance grows, and LHS’s advantage over simple random sampling (SRS) begins to diminish. In high-dimensional scenarios, achieving a representative sample with LHS can require exponentially more points to maintain the same precision, potentially making it less efficient than anticipated.

Challenges with Dynamic Systems

Another notable limitation of LHS lies in its static nature, which can be less effective for systems where variables have time-dependent relationships or feedback loops. LHS operates under the assumption that each variable can be sampled independently within its interval, which is reasonable for many static or quasi-static systems. However, in dynamic systems—such as those seen in financial markets, climate models, or real-time simulations—dependencies between variables often evolve over time, meaning the state of one variable may directly influence the others.

For example, in a climate model where temperature, humidity, and wind speed are interdependent and change over time, simply sampling each dimension independently may miss critical interdependencies. Mathematically, if we denote a system state at time \(t\) as \(\mathbf{x}(t) = (x_1(t), x_2(t), \dots, x_d(t))\), then dynamic relationships between variables \(x_i(t)\) might require joint distribution sampling, something that LHS in its classical form doesn’t inherently accommodate.

For dynamic models, we would ideally sample from the conditional distributions \(P(x*i(t) \vert x*{-i}(t))\), where \(x\_{-i}(t)\) represents the set of all other variables at time \(t\). However, traditional LHS treats each dimension independently, lacking the ability to conditionally update samples based on evolving states of other variables. As a result, alternative sampling techniques—such as sequential Monte Carlo (SMC) or particle filtering, which adapt to these dependencies—are often more appropriate for dynamic systems.

Addressing Dependencies and Dimensionality Constraints

One way to address these limitations is by hybridizing LHS with other sampling techniques. For high-dimensional spaces, combining LHS with stratified sampling or Sobol sequences can mitigate the curse of dimensionality, ensuring better coverage in each dimension without requiring an impractical number of samples. In dynamic systems, integrating LHS with adaptive sampling techniques, where the sample distribution updates based on real-time data, may offer a way to retain the efficiency of LHS while accommodating evolving dependencies.

Demo

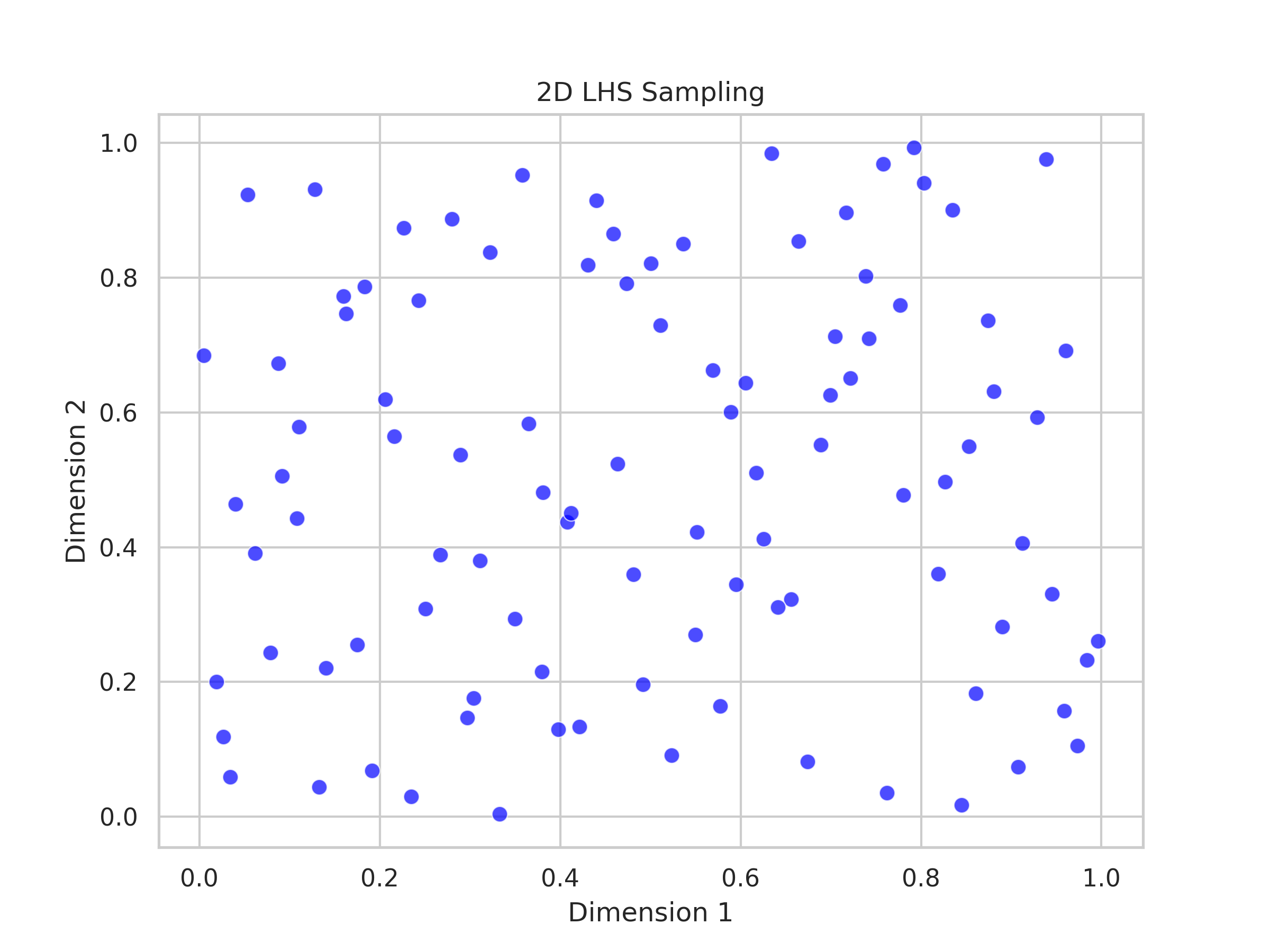

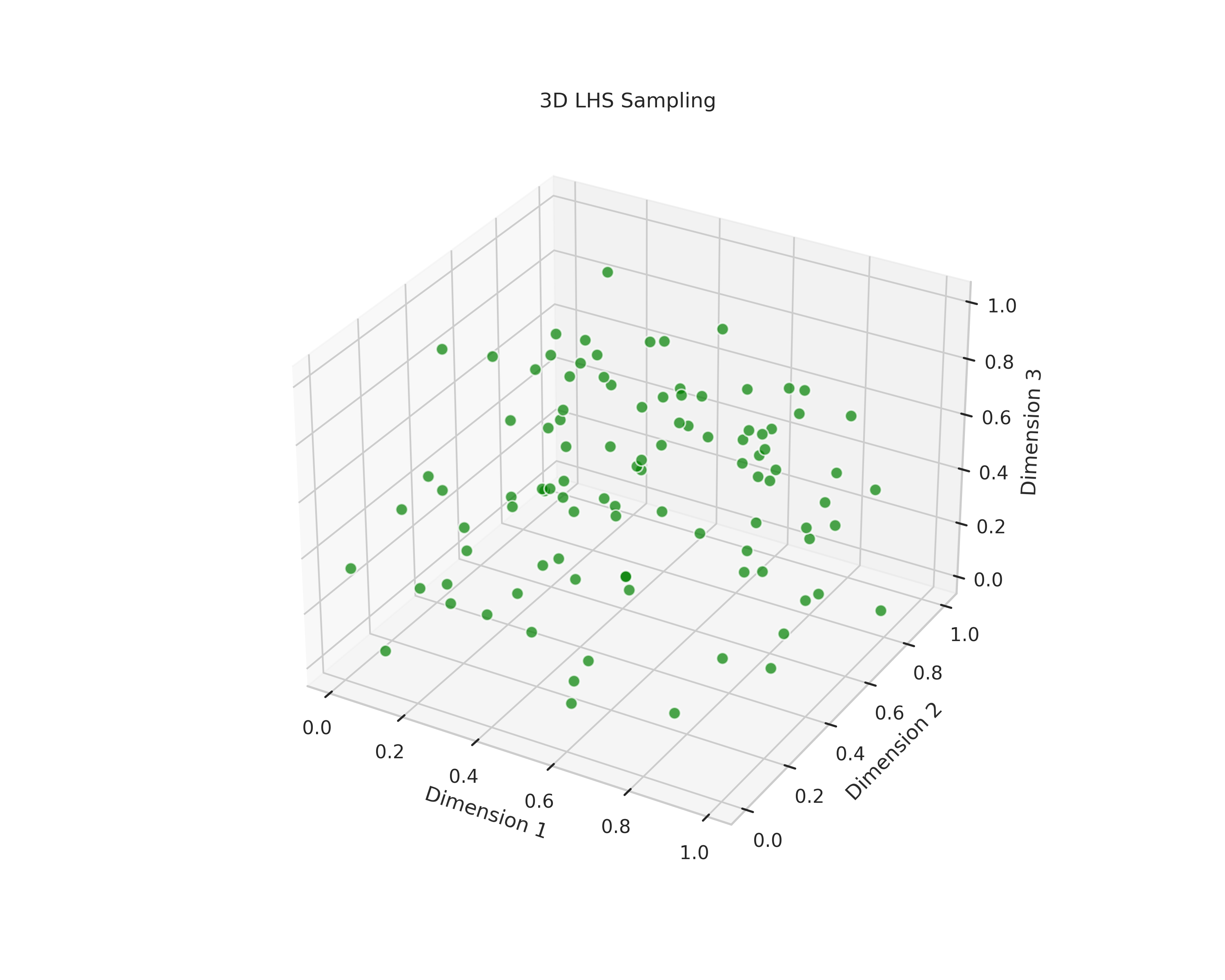

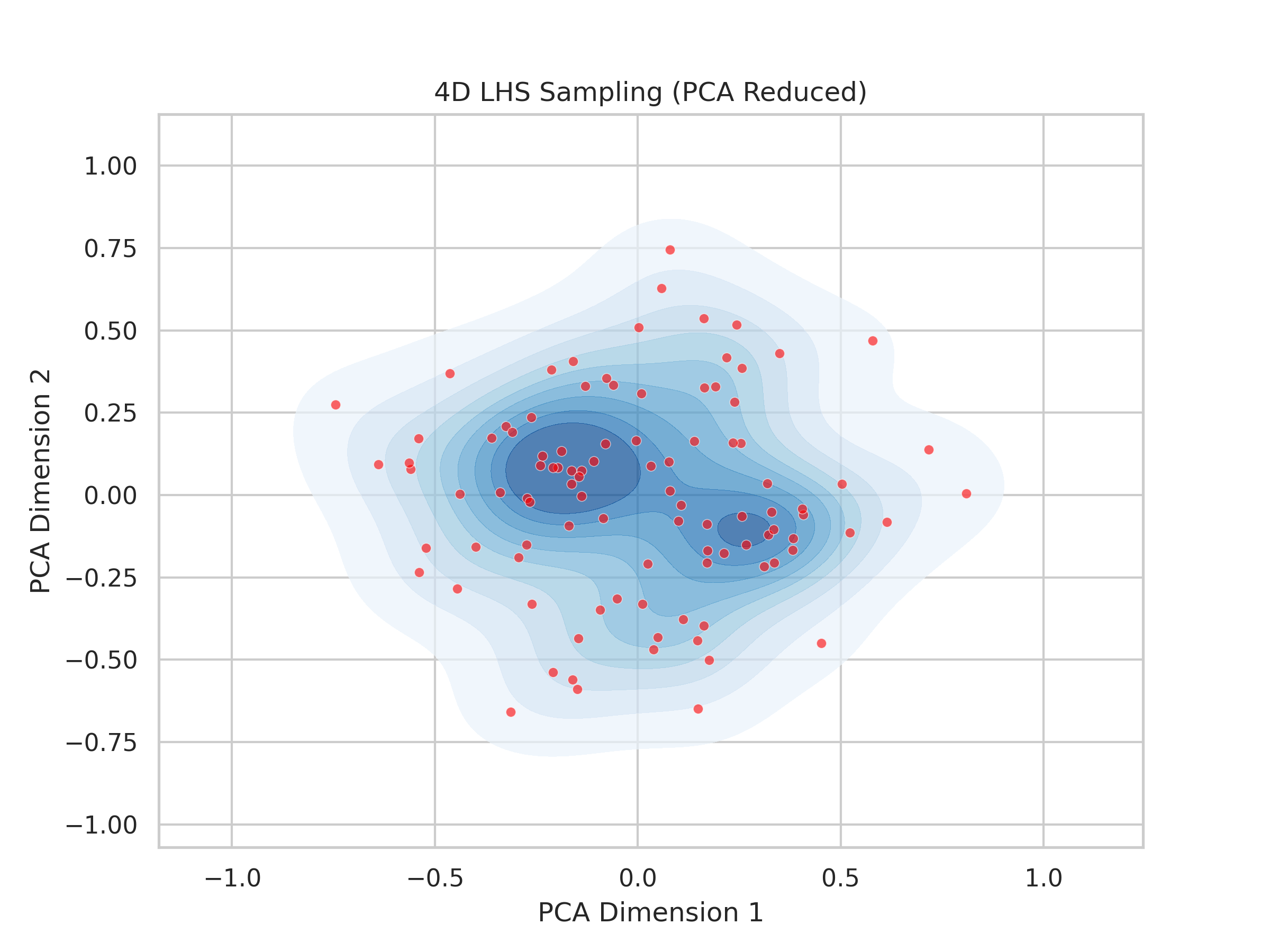

Here’s a demonstration of LHS across different dimensions. In 2D, we see LHS distributing sample points evenly across the grid, ensuring each part of the space is represented. In 3D, this principle extends gracefully, capturing a well-balanced spread across all three dimensions. Finally, in 4D, we employ dimensionality reduction to visualize the sampling density, revealing how LHS continues to provide comprehensive coverage even in complex, multi-dimensional settings.

Updated on June 22, 2024: Additionally, the PCA method used for dimensionality reduction in 4D sampling is detailed with examples in our latest blog post.

import numpy as np

import seaborn as sns

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

from mpl_toolkits.mplot3d import Axes3D

from sklearn.decomposition import PCA

from scipy.stats import qmc

# Set global Seaborn style for consistent visualization

sns.set(style="whitegrid", palette="muted")

# Number of samples and different dimensions to illustrate LHS sampling

n_samples = 100

dimensions = [2, 3, 4]

# Function to generate Latin Hypercube Sampling points

def generate_lhs_samples(dim, n_samples):

sampler = qmc.LatinHypercube(d=dim)

sample = sampler.random(n_samples)

return sample

# Function to reduce dimensions using PCA (for high-dimensional data)

def reduce_dimension(data):

pca = PCA(n_components=2)

return pca.fit_transform(data)

# Plotting 2D LHS samples

def plot_2d_lhs(samples, title="2D LHS Sampling"):

plt.figure(figsize=(8, 6))

sns.scatterplot(x=samples[:, 0], y=samples[:, 1], color="blue", s=50, edgecolor="w", alpha=0.7)

plt.title(title)

plt.xlabel("Dimension 1")

plt.ylabel("Dimension 2")

plt.grid(True)

plt.show()

# Plotting 3D LHS samples with a 3D perspective

def plot_3d_lhs(samples, title="3D LHS Sampling"):

fig = plt.figure(figsize=(10, 8))

ax = fig.add_subplot(111, projection='3d') # Create 3D projection

ax.scatter(samples[:, 0], samples[:, 1], samples[:, 2], color="green", s=50, edgecolor="w", alpha=0.7)

ax.set_title(title)

ax.set_xlabel("Dimension 1")

ax.set_ylabel("Dimension 2")

ax.set_zlabel("Dimension 3")

plt.show()

# Plotting 4D LHS samples reduced to 2D with density map

def plot_4d_lhs_with_density(samples, title="4D LHS Sampling (PCA Reduced)"):

# Apply PCA to reduce the 4D data to 2D

reduced_samples = reduce_dimension(samples)

x, y = reduced_samples[:, 0], reduced_samples[:, 1]

plt.figure(figsize=(8, 6))

# Plot density heatmap using kdeplot

sns.kdeplot(x=x, y=y, cmap="Blues", fill=True, thresh=0.05, alpha=0.7)

# Overlay the scatter plot for sampled points

sns.scatterplot(x=x, y=y, color="red", s=20, edgecolor="w", alpha=0.6)

plt.title(title)

plt.xlabel("PCA Dimension 1")

plt.ylabel("PCA Dimension 2")

plt.grid(True)

plt.show()

# Loop through the specified dimensions and generate the corresponding plots

for dim in dimensions:

samples = generate_lhs_samples(dim, n_samples)

if dim == 2:

# Plot for 2D LHS sampling

plot_2d_lhs(samples, title="2D LHS Sampling")

elif dim == 3:

# Plot for 3D LHS sampling with 3D view

plot_3d_lhs(samples, title="3D LHS Sampling")

elif dim == 4:

# Plot for 4D LHS sampling after PCA reduction with density visualization

plot_4d_lhs_with_density(samples, title="4D LHS Sampling (PCA Reduced)")

Wrapping It All Up

LHS is, without a doubt, an impressive technique. It’s one of those methods that shows just how much smarter sampling can be than a simple “grab a few random points and hope for the best” approach. By strategically covering each dimension and ensuring no corner of our data space is left unexplored, LHS brings precision and balance to the chaotic world of complex systems. Whether you’re testing car engines, predicting financial risk, modeling climate change, or designing clinical trials, LHS has a unique knack for extracting the most insight with the least effort. It’s efficiency and elegance wrapped into one neat package.

That said, LHS is not a cure-all. As we explored, it starts to stumble in high dimensions, where the dreaded curse of dimensionality can make even the most elegant sampling methods feel a bit sluggish. And when variables are in flux, like in dynamic systems, LHS’s simple structure can’t quite capture the dance of interdependencies over time. In those cases, it’s like trying to catch a shadow—by the time you sample one point, the system has already changed. But here’s the fun part about a method like LHS: it has this air of adaptability. While it might not suit every situation perfectly, it can be hybridized, adjusted, and even reinvented to suit new needs. I think that’s why it’s so appealing to both engineers and data scientists alike.

Enjoy Reading This Article? Here are some more articles you might like to read next: